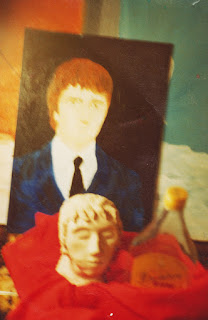

This is the suit I wore to the formal but I'm not dressed up for that here. What I'm trying to do is take a newspaper photo of myself for my photography folio. I put a flouro desk lamp to one side (I thought it was blasting) set Dad's Pentax to its most punishing light reception, used the flash and then under exposed in the darkroom. I wanted it to look like front page news. Kind of worked.

What I'd wanted was a black OR white photo. The greyless drama of the megaflash on suit and tie always said big news to me: rock star tours, prime ministerial dismissals. Taking a photo like this (ended up trying it for days) was important to me at the time as I was doing a photography semester for Art at school and this was the only idea I'd had that was remotely signature. I was no better at expressing anything with a camera than I was with oil paint and canvas. It wasn't just a matter of skill. There was something deeper going on.

In the end with both the painting and the photography I had to admit to myself that I had nothing to say through them. The admission was a difficult one. Almost all my life to date had been recorded visually. There wasn't just Dad's photography or super-8-ing but my drawing. All my family draws well but only a few of us persisted with it beyond childhood. For me it was a way of representing the phases and days emotionally, sublimating them into scenes that covered the entire sketchpad page, even between the wire coils of the binding. Each one was a newly designed space, a walk in memory. The subject matter was usually from a European historical period (most often 18th century) but its emotional content took me straight back to the motivation for the drawing. See? Something to say and a medium. Simple.

This need went numb and left me on the way to seventeen. Once there I was concentrating more on music, having taken it up as a school subject and gained more or less continued access to my brother Greg's old electric Maton Flamingo and his 15 watt Coronet transistor amp. Add a really nifty fuzz box by Companion to that and drawing as an emotional outlet starts looking like macramé.

Still, oil paint loomed large as a possible means of lifting myself into something that might be supported by lifestyle. But it was a dead end. Without a well defined motive, my creative work suffers from impatience. Oil paint takes a long time to dry in Florence. In Townsville's constant gluey humidity it takes twice as long as that. The other thing I didn't get was colour. My chief weapon in drawing was the line. You don't have to rely on line to draw with pencil but I liked it. Not just the line but the scission of it, I left gaps where the light would forbid a clear line in real light (something I do to this day).

What this means is that not only did I have to cope with a slimy, squashy medium in oil paint but I had to learn a lot of new skills so I could suggest depth and the effects of light. I only just passed the subject at school and put my oils away, never to look at them again.

Here's why:

And then there was photography.

The one thing I discovered about photography was that if I did it well I could achieve the thing I liked about pencil drawing: I could suggest a line rather than burden a picture with too much definition. Which brings us to the picture above. That's me trying to do a pencil drawing with a camera. Here are some more.

I can't remember if I asked Jo to dance like that. Maybe I just lucked out with some unusual movement and hit the shutter. Whatever, when I saw it emerge from the whiteness of the sheet in the developer I knew I'd got something good. It might not be obvious.

Because Jo is doing something flamboyant Darren is looking down, not at her feet but away from my camera which he knows is with me on the branch of the tree overhead. He's not shy. He's cool.

Minutes later. Darren is telling Jo to ignore me but she's laughing.

Minutes later. Darren is telling Jo to ignore me but she's laughing.I knew at the time that these were not presentation photographs. Nor were they so characterful that they transcended all the mistakes I made in taking and processing them. But to me they recorded things I knew about the people in them, their personality, their style.

To me it was something I could never achieve with pencil and paper, a kind of life drawing.

But that's the extent of it. I took a fair few more character studies of friends and also the kids who played sport on the oval at lunch time. The latter was a kind of protest against .... I'm trying to recall that but I think it was just a stand against physical culture. Well, that's what I was like. Anyway, if you look at those pictures you'll really only just see people, in the refectory, looking out of windows, or teams of them following a football in the noonday glare.

My problem is that, along with the painting (oh, dig that setup in my photo of an oil painting I was attempting: something ironic in the portrait of an imaginary conformist, the failed clay bust and the empty half bottle of Bundy in the foreground in case you missed how bohemian I was)...along with the painting and the drawing and anything that wasn't easy like music, I had almost nothing to say. This is before you get to any of the poetry I was writing at the time, having discovered the dramatic monologues of Robert Browning and T.S. Eliot. I'll spare you that, here at least.

But the memory of it gave me Marty's key. I said below that it was "failure" and that's true but as Gail's arc has to do with her control, Marty's must be about his willingness to confront his limits. I tried a few things for this. One involved killing a baby but I don't need that much now. I already had his camera around his neck when I thought of that; a pretty clear case of ignoring the props you've already put on stage.

The year ended and I did alright in the photography semester. Those who did better had put the work in, in their presentation and by paying attention to what they needed to do to take decent photographs. After school I took a few rolls in colour but didn't even bother to have them developed. If they are still in my antiquary they are probably as sticky as ripe tamarinds.